Where Does Our Water Come From

by Cassidy Mantor

Saguaro cacti and layers of sun-bleached limestone. Barren, rusted landscapes. Southwestern skies from Georgia O’Keeffe paintings and Edward Abbey’s cloud studies. Dramatic Wylie E. Coyote-style talus slopes and cliffs dropping off into the Colorado River. The Grand Canyon. The red rocks in Sedona and Moab. Coachella. Palm Springs. Las Vegas. Arches and Canyonlands National Parks. The desert is an oft-romanticized part of the American West for good reason.

The landscapes are profoundly different from other more hydrated parts of our country, like Montana’s Flathead Valley and Glacier National Park. Except that – believe it or not – much of Montana is actually an arid climate. We are familiar with marooned travelers thirsting their ways through the Mojave or Sonoran Deserts to find one drop of water. That narrative doesn’t exist for Montana. It should.

As I write this in late August, Flathead County and neighboring Glacier County are in a state of Severe to Extreme Drought, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor, a resource that collects data in partnership with NOAA and the USDA. These counties cradle Glacier National Park and comprise the only region in the Northern Rockies that is in Extreme Drought. The only other place in the western U.S. with the same extreme degree of water shortage is in the Chihuahuan Desert on the New Mexico/Texas border and we expect it there.

When we think of Glacier National Park, we think of alpine meadows, rushing blue-green rivers, and spectacular lakes, not the dry and barren land of the desert Southwest. But this year, our “Crown of the Continent” and the surrounding Flathead Valley have more in common with those rusted landscapes as the region faces one of the driest years on record. This is particularly concerning since the National Park Service considers Glacier’s water the headwaters of North America. From one point in the park, a droplet will theoretically split one of three ways and go to the Pacific, the Atlantic, or Hudson Bay. Extreme drought in this region has a catastrophic effect on our entire continent’s watersheds.

Where does our tap water come from?

Whitefish gets most of its water from the neighboring Haskill Basin, a 3,000-acre conservation easement of pristine lakes, rivers, and streams. In the summer months when water is low, Whitefish Lake provides an alternate source of water for the town. Upstream of Whitefish Lake, the Stillwater State Forest has a healthy watershed for hunting as well as recreational uses. As the population continues to grow and put an increased demand on these water sources, the Trust for Public Land helped add 13,000 acres to the Stillwater State Forest, thereby expanding Whitefish’s water sources. Kalispell relies on groundwater within city limits and four storage reservoirs.

But why are we talking about water now? Between Flathead Lake and Whitefish Lake, not to mention Glacier’s 131 named lakes, it is easy to relax into a false sense of security about water in the Flathead Valley. In reality, Montana receives on average 15 inches of rain each year, making it the sixth driest state in the country behind the stereotypical desert climes of Nevada, Utah, Arizona, Wyoming, and New Mexico. While Whitefish receives about 22 inches of rain per year, Kalispell receives closer to 15. Montana’s position and high temperatures make the entire state prone to drought – not to mention fire.

At the risk of sounding like an environmental Chicken Little, unless we adopt widespread water conservation practices, Whitefish is on track to run out of water. This August, the Whitefish Pilot reported that Whitefish Lake water levels were at historic lows. Montana FWP and Whitefish Parks & Rec advised people with boats larger than 20 feet – including large pontoons and wakeboard boats – to avoid the lake because it was too shallow.

Currently, Whitefish’s water supply infrastructure is at a maximum capacity. This puts severe stress on the City’s infrastructure and operations. Conservation practices and wasting less water will reduce the peak summer demand and costs of supplying water, as well as the life of the City’s water infrastructure. Using less water also reduces our impact on the environment and preserves resources for future generations who live, work, and play in Whitefish.

It’s a shocking proposition, but equally surprising is how little rainfall the Flathead Valley gets naturally. Water has always been one of the most precious resources in the West. Now, as more people move to Flathead County, WHJ is leading a discussion on responsible water use and conservation. You built your dream house here because you loved the place. Now it’s time to understand how to take care of the place and what it will take to keep the dream alive.

What can you do?

As part of the Climate Action Plan, the City of Whitefish instituted a General Conservation Ordinance that prohibits all outdoor watering between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m. The next stage of water shortage in the Flathead Valley provides procedures that include no watering on Mondays and staggered days to water based on even or odd street addresses. Excessive runoff leading to wet pavement is not allowed and all hoses should have positive shut-off nozzles. Fines for violating the restrictions escalate so that repeat offenders can have their water shut off. The Climate Action Plan is meant to address water use now, protect the current sources of the City’s water, and also diversify sources as the population continues to grow.

Smart landscaping is one of the main changes that we all can make to support the environment. Xeriscaping in the Flathead Valley means planting drought-tolerant species that will thrive in their native climate. Montana State University Extension published a yard and garden guide with more tips for selecting plants and soil saturation. Closer to home, the Flathead Rain Garden Initiative helps citizens in the Flathead Valley install native plant rain gardens in their yards. The gardens provide pollinator habitats and filter storm water to help prevent pollutants from entering Flathead Lake and other watersheds.

Hardscaping is another responsible way to add visual interest and benefit the environment. Pavers can divert rainwater and be laid to capture water and provide natural irrigation. Renovating and remodeling with high-efficiency shower heads and appliances and evaluating sprinkler and irrigation systems are also ways to prioritize water conservation in the home.

The City of Whitefish instituted a General Conservation Ordinance that prohibits all outdoor watering between 9 a.m. & 5 p.m.

“It isn’t about using less water, it’s about wasting less.”

–The City of Whitefish

Small Changes Add Up.

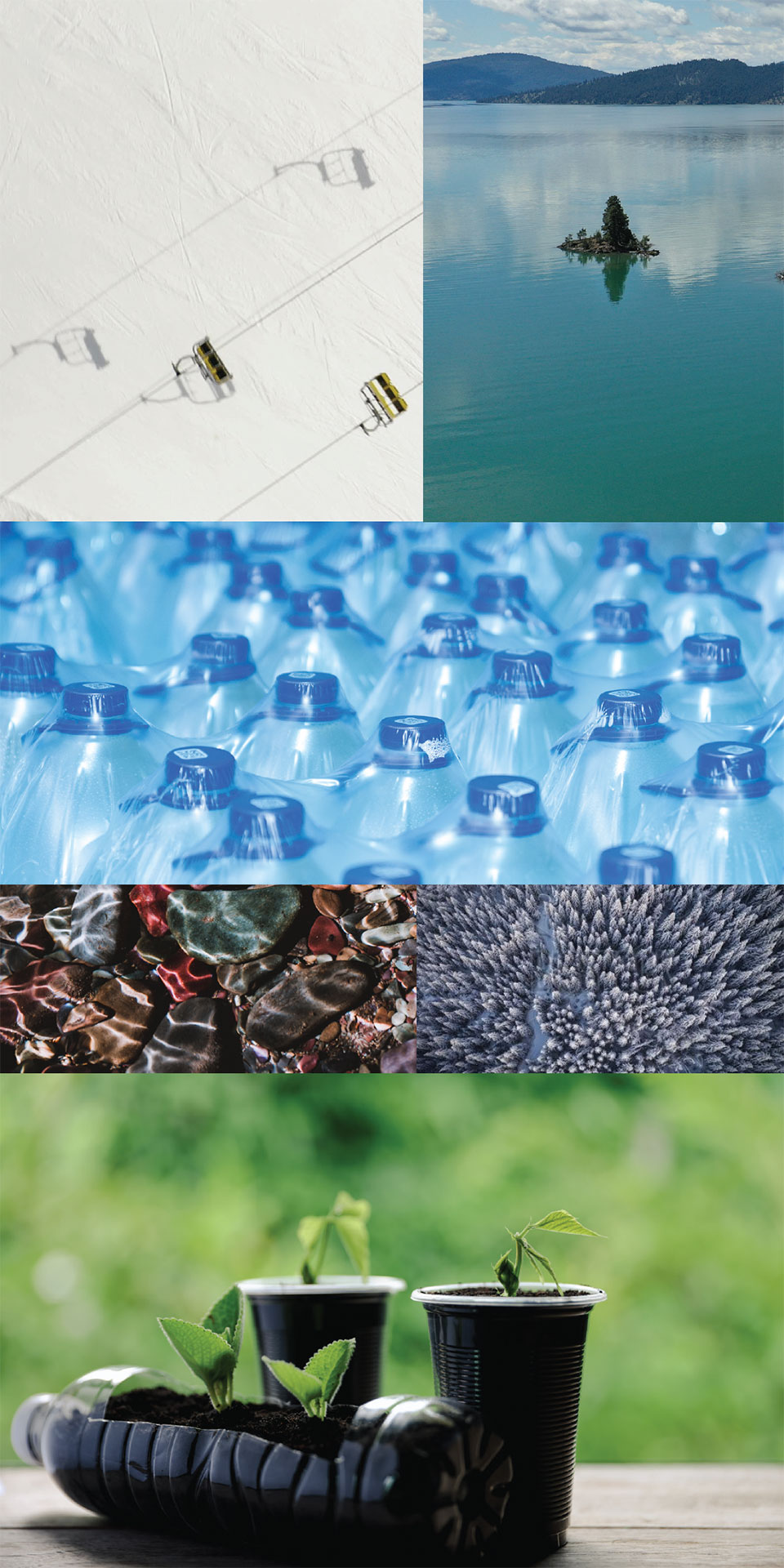

We’ve become accustomed to switching single-use plastic for reusable water bottles. Opting for no straw or using a compostable one minimally affects our lives but has a positive impact on the greater environment. Planting differently, composting, and educating ourselves on water use will lead to becoming a more responsible citizen. Water doesn’t just come from our taps. The sooner we shift our consciousness, the longer we will be able to enjoy the places we have come to love. The City of Whitefish says it best: “It isn’t about using less water, it’s about wasting less.”