Blurring the Lines

by Stephanie Dennee

An architect’s work is self-evident—right angles of concrete, wood, and glass. Less readily apparent is the work of a landscape architect, in part, because the natural materials they work with existed long before the human-made ones. For Field Studio, the often inconspicuous nature of their landscape architecture is also intentional. Their designs create a gentle evolution of place, and subtly set the tone for all of the property. Though home design may be easier to point to, the union of home to land through landscape architecture is equally essential. Field Studio achieves this union through a thoughtful blurring of the built with the natural and the property with land beyond its bounds.

Far more than the selection of plants or layout of irrigation, landscape architecture acts as an integrative component to building projects, putting the individual work of engineers, architects, ecologists, soil scientists, and property managers into collective relief. Bozeman-based Field Studio works across Montana and the greater Rocky Mountain region as that valuable synthesizing force for both residential and large-scale ranch projects. Founders Charlie Kees, Shara Kees, and Chris Keil, along with their team of three designers, approach their work from both an artistic and ecological standpoint.

“We start by embracing the site’s unique characteristics: ecosystem, geology, water, and native vegetation. Something about the site often drives the big picture of the design.”

–Charlie Kees, Co-Founder, Field Studio Landscape Architects

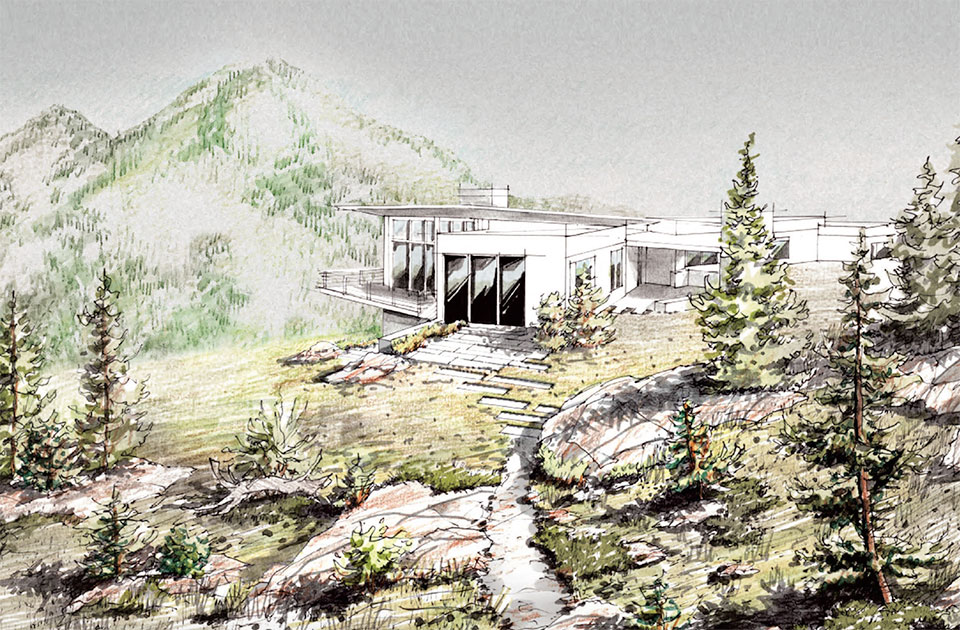

“We start by embracing the site’s unique characteristics: ecosystem, geology, water, and native vegetation,” says Charlie, who has worked in western landscapes for over 20 years. “Something about the site often drives the big picture of the design.” For a recent residential project near Red Lodge, the design was driven by a rock outcropping that created a dramatic ridgeline across the property. Field Studio worked closely with architects at Pearson Design Group to integrate the home and the site’s exposed bedrock. “The intention was for the structure to sit within the vein of rock. To make it feel as much a part of the geology as possible, we went to other portions of the property, harvested the same rock, and placed it around the building. The architecture then feels as though it is emerging from that geologic formation,” says Charlie. The result is a design that softens the line between built and natural, pulling the home into the land.

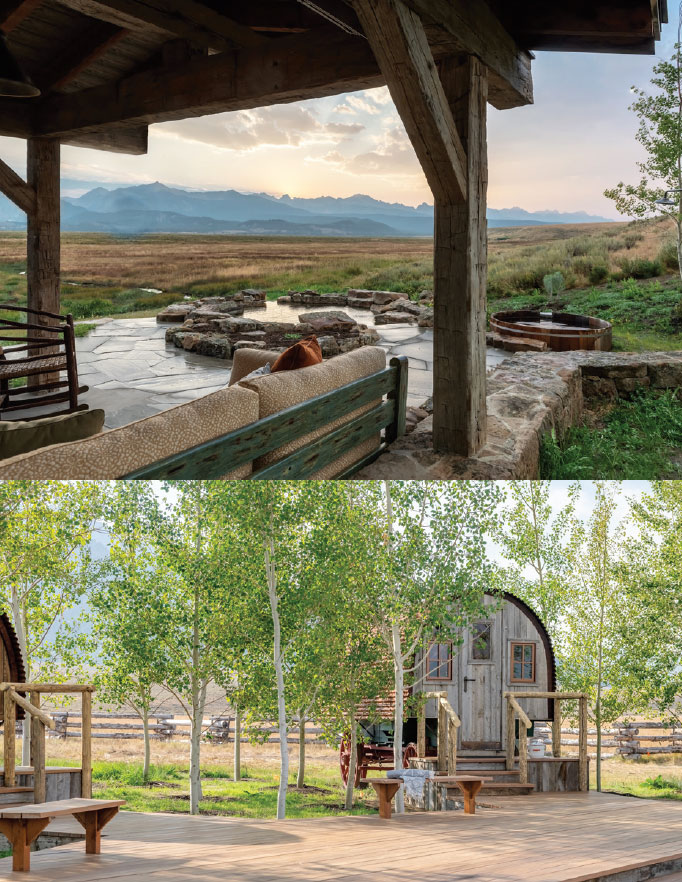

On another property, in the Sawtooth Valley, water provides the genesis of design. “The site plan centered on incorporating naturally existing hot springs and building dedicated springs for use near the home,” explains Chris, whose range of work experience includes everything from sagebrush restoration to urban landscapes in New York City. On one side of the property, aspen trees, hardscape, and dedicated planting beds provide visual cohesion and privacy screening for the main home and three guest cabins, designed by Miller-Roodell Architects. In contrast, on the other side of the homesite, a gentle slope of native grass and stone cradles a series of boardwalk paths to the homeowner’s hot springs sanctuary. Views to the Salmon River and Sawtooth Mountains beyond remain unobstructed. Of the fade from deliberate landscaping on one side of the property to the native landscape on the other, Chris says, “Our approach is to not over-design. We strive to do what is appropriate, having some restraint to let the property speak for itself while enhancing the authentic landscape.”

“Our creative ability to visually represent what the property will become helps everyone understand the narrative.”

–Charlie Kees, Co-Founder, Field Studio Landscape Architects

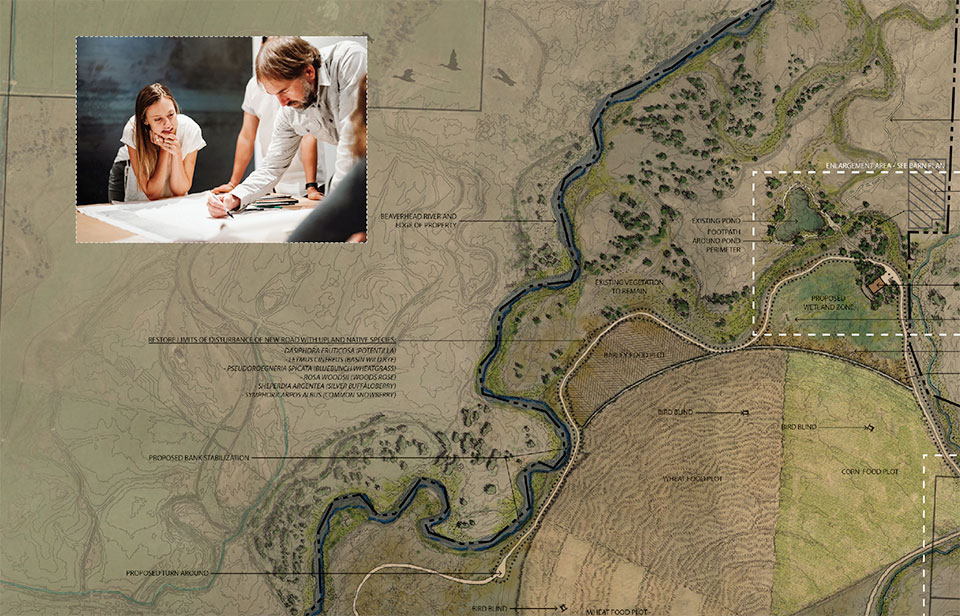

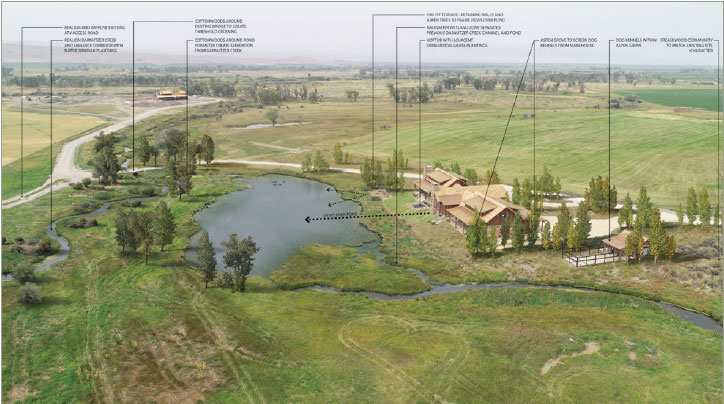

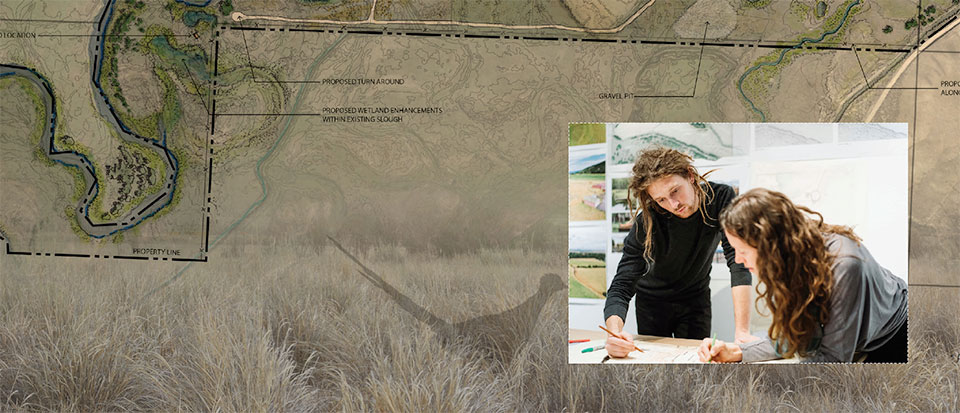

Water plays a leading role in much of Field Studio’s work, nowhere more so than the ranch projects for which the company is uniquely qualified. A recent Field Studio ranch project in the Beaverhead Valley began with a property owner’s goal of restoring aquatic and bird habitat on the land. Early on, the owner, who was attuned to the value in a landscape-driven site plan, contacted Field Studio to facilitate. Charlie explains the benefit of their early involvement in site planning. “This property has many components, intended to be executed over years. The initial goal was restoration of upland bird and waterfowl habitat, with home-building to follow.” The final master plan is both an art piece and a working program—a four-foot-tall, mixed-media rendering that merges drone imagery with pencil sketches and computer modeling to map several buildings, barns, and new ponds. The plan imagery also elicits the flora and fauna that the landscape will support over time. “One of the implicit challenges of landscape architecture is that it takes time for the vision to be fully realized,” says Charlie. “Master plans are a roadmap to that end, and our creative ability to visually represent what the property will become helps everyone understand the narrative. Things may change slightly with time, but the site plan will be the guidepost.”

When working with ranch designs that span thousands of acres with varied purposes, Field Studio considers the complexity of interdependent variables. “Our work requires an understanding of connected systems. For example, when working on projects that require riparian restoration, it is important to understand the context for the work—how the land is managed, the goals for the restoration, and what the long-term maintenance requirements entail. These aren’t necessarily the flashy portions of our work, but they are critical big-picture components,” says Charlie.

By focusing on big-picture components of landscape architecture, Field Studio acts not only as a steward for their clients’ properties but to the greater area, as well. In places facing rapid growth, the role of thoughtful design is never more imperative. “Good design is a critical component to sustainable growth,” insists Chris. “We design with the greater landscape in mind, meaning the proper placement of a home, assessing land implications, understanding the greater context of place, and selecting appropriate elements that fit within that context. When done well, the line between the natural and what is built is blurred, as is what lives on one piece of land with the land beyond.”

Charlie and Chris are quick to point out that none of this work is done by Field Studio alone. Charlie contends, “In many ways, landscape architects are generalists. We know a little bit about a lot of disciplines, and we know how to connect those disciplines. What we excel at is pulling specialists together while advocating for the overall intention of the property.” For some projects, that means a soil scientist and a fisheries biologist are on the same email chain. As varied as these specialists may be, their work is woven together on the property.

“For many of our projects, the goal is that a person experiencing the land won’t necessarily know anything has been designed. The more thought that goes into our work, the more it can disappear into the land.”

–Charlie Kees, Co-Founder, Field Studio Landscape Architects

Many of Field Studio’s days are spent on byways and backroads, visiting remote job sites from one corner of Montana to the other, and in states beyond. Charlie says the company name emerged as a nod to their nearly equal ratio of site to desk time. “Some of our best work is done in the field, in response to the material. Builders have set standards in materials that don’t exist for landscape architects. Every two-by-four is the same; every boulder is different. So, when stone or planting material is on-site, it’s an opportunity for us to see it and synthesize in real-time, finding the best way to use it.”

Field Studio ventures back on the road from a completed project having blurred the line between what has always existed there and what the land will be in time. This intentional blurring is, ironically, what brings their work into focus. Charlie says it best: “For many of our projects, the goal is that a person experiencing the land won’t necessarily know anything has been designed. The more thought that goes into our work, the more it can disappear into the land.”