Bozeman

A Summer Art Destination

by Michele Corriel

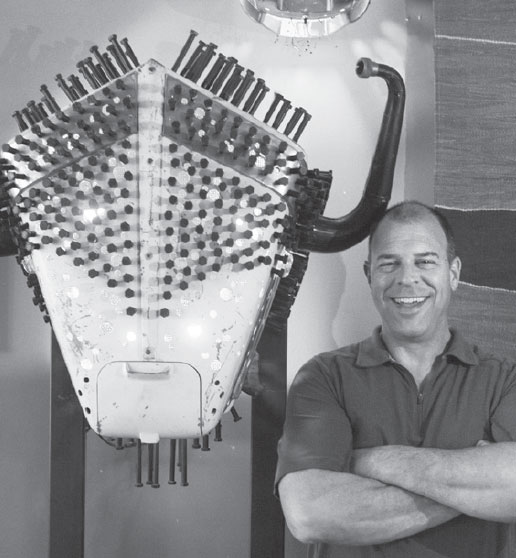

Above: Motorhead | 24”x 24”x 8” | Found Objects | Steve Bormes | Old Main Gallery & Framing

I don’t trust nobody but the land | Layli Long Soldier | Tinworks Art | Photo by Blair Speed

Bozeman, quickly becoming an “art” town, shines in the summer. The doors fling open, windows open wide, and everywhere from Main Street to the side streets fills with art enthusiasts. This summer will be no different. Here, we take a deep dive into two establishments that fly the art banner high and proud.

This summer, Old Main Gallery widens their array of artists. Aside from the usual amazing art (barbed wire art, serious oil paintings, and contemporary ceramics), this year’s offering includes Steve Bormes, a one-of-a-kind assemblage artist whose work is only limited by his imagination.

Then we have a real treat with the seasonal opening of Tinworks, which never disappoints. The art space shows contemporary installation work from artists both local and international. This year, the shows center around the idea of land, landscape, and community, with very special installations by renowned artists like ecological/land artist Agnes Denes and photographer Stephen Shore. Don’t miss this one. You might even want to visit it throughout the season, June – October, to fully immerse yourself in these works.

Steve Bormes creating in his studio

Old Main Gallery

Recycled, Reused, & Reimagined

Inside Steve Bormes’ Studio

“I use a lot of everyday items and present them in a different way; when people discover what’s in the piece, they get excited. When I’m scouting around, I start out with an empty Suburban and I expect to fill it. If I see a ranch with a lot of stuff, I stop to see if they’ll let me go through it all. I’ll use parts from cars, including taillights, fenders, and outboard motor cowls from boats.”

–Steve Bormes, Artist

Thanks to his love of spare parts, his sense of invention and a large dose of insomnia, Old Main Gallery artist Steve Bormes plays with ideas of utility and art. His assemblage pieces harken back to a time when broken things did not mean throwing them away.

“I use a lot of everyday items and present them in a different way; when people discover what’s in the piece, they get excited,” Bormes says. “When I’m scouting around, I start out with an empty Suburban and I expect to fill it. If I see a ranch with a lot of stuff, I stop to see if they’ll let me go through it all. I’ll use parts from cars, including taillights, fenders, and outboard motor cowls from boats.”

Buffa Lolo | 42”x 8”x 24” | Found Objects

Using the vernacular of mid-century cultural references, the contours of the 1950s and 1960s, Bormes’ assemblages reflect a sense of nostalgic comfort while also being whimsically futuristic, like the first episodes of Star Trek. Through his collector’s eye, his pieces take on personalities – whether it is a mask-like wall piece with colored lights emitting from the back, or aquatic life swimming in undiscovered waters – each one asks the viewer to consider it both as recognizable parts and as sculptures commenting on the many aspects of society.

For owner and gallery director Lindsey McCann, Bormes’ work opened up a more humorous aspect of her prior sense of the gallery.

“My personal aesthetic and view on art has always been rather serious,” McCann says. “However, after my recent cancer diagnosis, I’ve found my perspectives on many things changing, art being one of them.”

Facing something as serious as cancer has McCann looking for the lighter side of art.

“Taking things too seriously narrows my life experience,” she says. “Capital A Art isn’t always a fine oil painting or highly-valued bronze sculpture. Art is a feeling, a story, a message, a path for connection and discussion, a way to build community, a laugh, or a tear. Steve’s work is full of story, of connection to communities and for me personally, smiles. Every voice needs to be heard, it’s as simple as that.”

Pony Tale | 32”x48”x9” | Found Objects

“My parents threw us in a 1970 Winnebago. We were just piled in there. They took us mostly to all the churches, the ones with cool art, and great architecture. We stopped at lots of art museums. But I never wanted to draw or anything like that.”

–Steve Bormes, Artist

Although his work can bring about a feeling of joy, it also becomes a comment on our throw-away culture, our discarding of childhood dreams, and the celebration of pure imagination in a very tactile form.

For Bormes, the pieces “come alive” once they are plugged in when the light paints each environment beyond the boundaries of a piece. He likes to point out that when his pieces are incorporated into art collections, once the night falls, his pieces take center stage.

“I strive to combine components born of engineering with an artistic approach to light, to create pieces that both celebrate the original ingenuity of their creators and yet transcend a static presentation of that work,” he says.

Behe Moth | 59”x75”x31” | Found Objects

It is hard not to conjure some kind of mad scientist, a friendly version of Dr. Doom bringing his spare part robots to life with light. Bormes works in his studio surrounded by vacuum parts, truck lids, rusty metal and shiny things, pieces of thrown-aside wood, spiky knitting needles, bullets, found nails and corn snouts (the triangular steel parts on the front of a corn combine that push between the stalks). At the moment, he admits to a VW Beetle fetish.

“I collect in my studio, storage unit, and trailer,” he says. “I look for cool shapes … I really love things I’ve never seen before. New things attract me.” New to him, not brand-new, naturally.

Originally, from South Dakota, Bormes studied biology and math at the University of South Dakota. He also worked a variety of jobs including as a club bouncer, a communicable disease specialist, a salesman, a certified arborist, and an international textile and antiquities buyer. All these aspects contribute to his unique perspective on collecting and creating.

“It was more fun to create a hinge for something than to go the store and get one. It was a thrill. In my pieces, there are a lot of thrills like that.”

–Steve Bormes, Artist

“When I started working on the reservations in South Dakota selling office supplies, I found myself drawn to the art,” he says. “No one ever talked about it back then. That lasted for six years. Then I started a tree business. So, I became an arborist, and I would talk to the owners into not chopping their trees down. Instead, I pruned them and made them look good.”

That seems to be a bit of a turning point for Bormes. He began making giant fish out of chicken wire and hanging them from the trees he worked on. “The art was just coming out of me,” he says. “I didn’t even realize it.”

As things go, Bormes met Hassan, a Turkish rug dealer. “I bought six rugs – they were another form of art.” Before he knew it, he was traveling with Hassan across the country selling Turkish rugs.

One day a restaurant owner asked him to refurbish their lighting. Because he was traveling to Turkey, and picking up things he found interesting, Bormes took antique butter churns from Turkey and hung them like a swag light. “I started putting groovy round holes in them and it was like the Flintstones meet the Jetsons. No one had ever seen anything like them before,” he says.

After two art professors told him they liked his work, he began to rethink everything.

Scaredy Kat | 11”x18”x12” | Found Objects

“I let my hair down, focused on my assemblages,” Bormes says. “I wanted to be a hippie millionaire as a kid and that’s what I’m trying to be still.”

For his Montana show this summer, Bormes wants to make creatures. All kinds of creatures could be derived from his biggest inspirations like Chitty Chitty Bang Bang or Dr. Seuss. They could be imagined underwater fish from the deepest unexplored trenches. One thing they most definitely will be is straight from the mind of Bormes.

Bormes grew up in a family with eight children and parents who loved to travel and loved art.

“My parents threw us in a 1970 Winnebago,” he says. “We were just piled in there. They took us mostly to all the churches, the ones with cool art, and great architecture. We stopped at lots of art museums. But I never wanted to draw or anything like that.”

With eight kids there was no money. His father would have everyone collecting stuff from the neighborhood and together they built the thing they needed from scratch. “My dad had a garage of vacuum parts, old telephone parts; he could fix anything with those pieces. It was more fun to create a hinge for something than to go the store and get one. It was a thrill. In my pieces, there are a lot of thrills like that.”

He came up with a name for the style of his work, “Prairie Funk,” he calls it.

When thinking about his Bozeman show, he is considering making caribou. “I have these gigantic motorboat covers, old snow skis that will be the antlers, with their twisted tips, and right now I have a hay fork in my hand, it looks like a big machete with two handles. If I make this caribou, he might have that for his spiky hair.”

Taking inventory of his collection around his studio, of the spare parts and springs, doohickies and gismos, Bormes knows he’ll create pieces that are just waiting to be made.

Inside Steve Bormes’ Studio

Tinworks Presents

The Lay of the Land:

A contemplation of contemporary artworks embedded in the idea of place

Wheatfield – A Confrontation: Battery Park Landfill, Downtown Manhattan – With Agnes Denes Standing in the Field, 1982

Photo: John McGrail, courtesy Agnes Denes and Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects

“This Wheatfield is more personal. It’s inspiring people to communicate what’s possible, to hold people together beyond politics.”

–Jenny Moore, Tinworks Director

Wheatfield – A Confrontation: Battery Park Landfill, Downtown Manhattan – With Statue of Liberty Across the Hudson, 1982

Copyright Agnes Denes, Courtesy Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects

Sometimes it is not the work itself that emanates beauty but the idea behind the piece. Such is the case with Agnes Denes’ Wheatfield. Although who would deny the beauty of a wheatfield bending to the wind and reaching for the sun? Dig a little deeper and Denes’ philosophical impetus for the installation washes over all of us. She blankets us with community and sustenance and begs the question of conservation and of place.

In 1982, artist Agnes Denes planted a two-acre wheatfield in the shadow of the World Trade Center – an artwork dealing with corporate greed and world hunger. According to Denes, “Wheatfield was a symbol, a universal concept. It was an intrusion into the Citadel, a confrontation of High Civilization. Then again, it was also Shangri-La, a small paradise, one’s childhood, a hot summer afternoon in the country, peace, forgotten values, simple pleasures.”

From summer to fall, the art space Tinworks teems with multiple viewpoints from seven artists near and far. This year’s germinating theme springs from wild and nurtured places underfoot.

Forty-two years later, Denes, who will celebrate her 93rd birthday in May, is revisiting those ideas from a different perspective. A crop of winter wheat was planted this past October in Tinwork’s field at the corner of Ida and Cottonwood Avenues in Bozeman’s northeast neighborhood. It will grow through the summer, tended by the Tinworks’ team and community volunteers, be harvested in the fall, and processed into flour by small-scale mills set up on site.

“This summer’s program at Tinworks started with Agnes’ Wheatfield–An Inspiration. The seed is in the ground,” Tinworks Director Jenny Moore explains. “It’s a way to recast her iconic artwork in a different context and time. It’s an opportunity to inspire us to think about land value, how to treat the land, and to look for solutions to environmental challenges that can endure.”

Wheatfield for Tinworks utilizes the land not only as an art installation, but is also meant to start a conversation, to spark discussion of how to understand the land that surrounds us. The artist invites the community to plant spring wheat in fallow land available to them in solidarity with the wheatfield at Tinworks’ site.

“This Wheatfield is more personal,” Moore says. “It’s inspiring people to communicate what’s possible, to hold people together beyond politics. Agnes is not trying to superimpose her will on the land (the way Agnes felt lot of the male artists of the Land Art Movement did), instead she is working with the land. It’s ecological. It’s a way to think about how land defines space and place.”

Wheatfield—An Inspiration. The seed is in the ground. Agnes Denes for Tinworks Art 2024 | Photo by Blair Speed.

Among the other artists sharing their work this summer at Tinworks, multimedia artist Lucy Raven examines the phenomenon of glacial dam breaks that leave their mark on the land over a geological time scale through large-scale works and video.

“She’s recording a natural force that shapes the land,” Moore says. “By recreating the conditions of dam breaks, and then using the sediment left behind, imprinted on silk fabric, she recalls the natural processes that have sculpted the landscape.”

A kind of geological history as art.

Stephen Shore | Meagher County, Montana, July 26, 2020 46°11.409946N, 110°44.018901W | pigment print | 24” x 32” | From Topographies: Aerial Surveys of the American Landscape | Courtesy the artist and 303 Gallery.

“I’ve taken a number of pictures over the years where I’m trying to see topographical transitions; every now and then from eye level you can see it but it’s never as clear as seeing it from above. The recurring theme is to see how a stream passing through one neighborhood to another neighborhood changes.”

–Stephen Shore, Photographer

Renowned photographer Stephen Shore’s exhibition highlights a series he produced during the pandemic.

His goal was to write a memoir of his groundbreaking career titled Modern Instances: The Craft of Photography, published in 2022/2023. His other goal was to start working with a drone.

“I’ve taken a number of pictures over the years where I’m trying to see topographical transitions; every now and then from eye level you can see it but it’s never as clear as seeing it from above,” he says. “The recurring theme is to see how a stream passing through one neighborhood to another neighborhood changes.”

Stephen Shore | Madison County, Montana, August 1, 2020. 45°36.161521N, 111°34.342823W | pigment print | 24” x 32” | From Topographies: Aerial Surveys of the American Landscape. Courtesy the artist and 303 Gallery.

Shore’s contemplations of the landscape shifted when using his Hasselblad camera attached to a drone brought a new perspective to the work.

“A lot of landscape photography is abstract, taken straight down, I don’t do that,” he says. “I wasn’t interested in that. I was interested in the content and the organization of the content. I’m not approaching it with a theory. I’m looking at it through specific instances. And what I’m seeing is that the relationship varies.”

The drone expands Shore’s perception with a point of view he couldn’t get otherwise. “The method of working with a drone also expanded how I see. If I’m on the street, I know what is going to come into the frame,” he explains. “When I’m working with a drone, I’m looking at a monitor and I don’t know what’s outside the frame. There’s a feeling of exploration that I love.”

Moving to Montana in 1980, it took some time before Shore felt he understood enough about the land and the feelings of being in that place before he could start photographing it in any meaningful way. “You have to get to know a place before you can have perceptions about it,” he says.

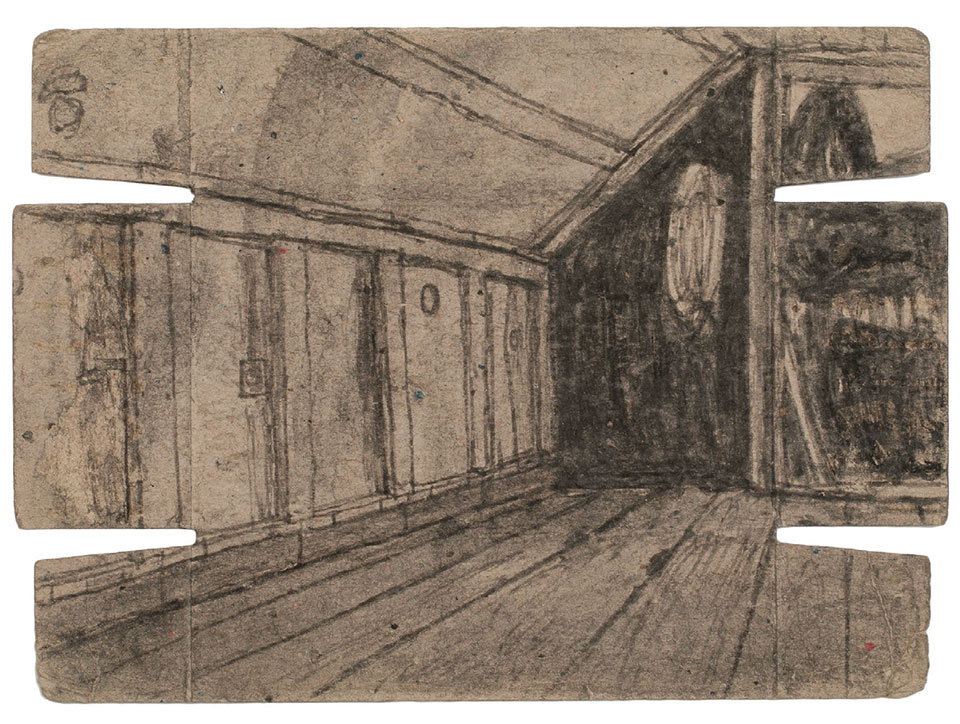

Untitled (attic/farmscape), n.d. | James Castle | Found paper, soot | 5 1/4” x 7 1/4” | Courtesy James Castle Collection and Archive LP

James Castle (1899 – 1977) is generally considered an “outsider artist,” but perhaps his work might instead be understood as Isolated Art, as well as a commentary on the power of storytelling and personal art.

“Castle deals directly and literally with place,” Moore says.

Growing up deaf in turn-of-the-20th-century Idaho, in and among a hearing community, Castle was clearly compelled to share his narrative experiences with the world. His artistic tools included found materials like sharpened sticks, apricot pits, pieces of cotton and broken pen nibs, spit, and soot scraped from a woodstove. His work feels like it is strained at the edges, jumping from behind. The subjects of everyday life come across in his work as elevated, not mundane.

“His work represents metaphysical depictions of the land,” Moore says. “He makes both exterior and interior spaces feel very present and intimate.”

“His work represents metaphysical depictions of the land. He makes both exterior and interior spaces feel very present and intimate.”

–Jenny Moore, Tinworks Director

Asterisms | Chris Fraser, 2019 | Tinworks Art | Photo by Blair Speed

For a different take on place, sound artist Robbie Wing uses railroad ties to understand the perception of sound and the spaces sound occupies. Using railroad ties reclaimed from the Tinworks site, Wing weaves together the aural world with the material landscape.

“The physicality of sound can tell historical narratives,” Wing says. “I work with the idea of vibrational histories. The railroad connects many places across the U.S. and especially Montana. But those places have changed over time.”

Technically speaking, Wing will use the vibration of speakers and mics for feedback loops, by pulling those frequencies back and through the railroad ties so they can sing their own song. It’s a piece he calls The Cross Ties Song.

“I’ve been interested in railroad ties and other materials that are commonplace in landscapes,” he says. “They’ve entered into the vernacular of the landscape so much that we don’t really notice them. There’s this idea because of sounds’ physical nature, it can be frozen in time and the frequency itself can be seen as a living entity that has agency. I’m trying to put myself in a position with something that has its own agency; it’s telling us something.”

By agency, Wing explains, sound, uncontained, will spread in unexpected ways. “My question is, do I know how to listen to a landscape and what is it trying to tell me?” he says. “In Montana, I’m having to reconcile whether this place is even talking to me. The piece is letting them speak for themselves, in a way. I’ve set the process up to explore this idea. The exhibition will also include field recordings.”

Moore says the presence of the railroad in proximity to Tinworks’ site is among its distinctive elements. She is excited that Wing is using the acoustic properties of place and the history of the railroad to emphasize this connection.

“In Montana, I’m having to reconcile whether this place is even talking to me.”

–Robbie Wing, Sound Artist

In addition to these exhibitions, Tinworks continues to show Layli Long Soldiers’ lightbox installation, I don’t trust nobody but the land, which can be viewed on the façade of the former mill building at Tinworks’ site on Cottonwood Avenue.

“These exhibitions and installations are a continuation of a theme presented in last year’s exhibition, Invisible Prairie, which considered how we represent land and place,” Moore says. “In summer 2024, we will also continue a program history of inviting artists to work onsite, with artist-in-residence Wills Brewer, a ceramic artist, who will research the possibility of building a clay dwelling in place.”

Day Poem: Sun Mirrors | Layli Long Soldier | Tinworks Art | Photo by Blair Speed

Another use of the space will be a performance workshop based on Montana choreographer/dancer Mary Overlie’s The Six Viewpoints, led by Isabel Shaida.

“The Viewpoints approach both dance and theater as physical entities akin to natural landscapes that can be entered or traversed,” Overlie wrote in her 2016 book about her philosophy of movement. The six viewpoints—space, shape, time, emotion, movement, and story—combine to create a variety of dialogues between the dancers, within the dances, and the movements engage the audience in a surprising and powerful way.

“The Viewpoints approach both dance and theater as physical entities akin to natural landscapes that can be entered or traversed.”

–Mary Overlie’

Shaida/Overlie Workshop | Photo by Andy Lawless

The dates of the Six Viewpoints workshops are July 13-September 14, which culminate in a public performance September 7. Tinworks is also hosting a condensed one-day workshop before the second public performance on September 14.

Additionally, the choral ensemble Roots in the Sky will again perform at Tinworks in Chris Fraser’s ‘Asterisms’ installation July 6 and 7.

Tinworks’ exhibition season opens June 15 and runs through October 19.